|

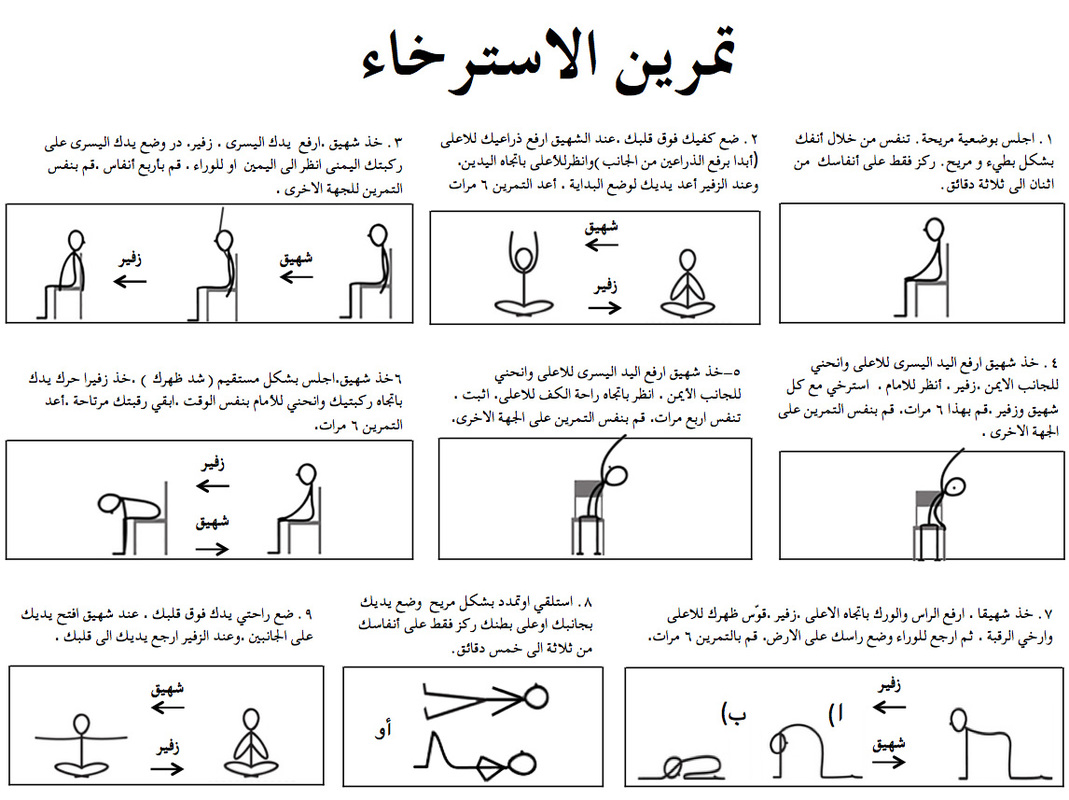

This article was originally featured on Seattle Yoga News, May 27, 2015. I spent this spring sharing yoga with Syrians seeking safety and refuge in southeast Turkey. I arrived well versed on the four-year Syrian crisis, prepared to teach yoga in Arabic and ready to be of service to people as they healed the wounds of conflict. When I arrived, the crisis was entering its fifth year and more than 220,000 Syrians had lost their lives. The news was always grim. Grief, distress and heartache were omnipresent when I arrived. But the most tangible sentiment I perceived was the sense of support and community that the Syrians brought to each yoga session. After only a few weeks of sharing yoga in local organizations, it became clear that their social spirit was their strongest source for healing. Yoga became a unique opportunity for them to connect with each other as they coped with distress from the crisis. Life in Turkey The Syrians who participated in my yoga classes had all endured immeasurable loss and survived harrowing circumstances. Many had watched in terror as their towns had been bombed or raided while their loved ones were imprisoned, executed or abducted. Many had fled after being targeted by the Syrian regime or extremist groups such as Daesh (the Arabic name for the Islamic State). The crisis disrupted all aspects of their lives; they were forced to postpone marriages, close family businesses and withdraw from university studies. The crisis unraveled the social fabric of everyday life; families were torn apart and communities were polarized by new religious and ethnic lines. One participant shared that her husband was en route to seek asylum in another country — a dangerous journey — and she had not heard from him in one month. Unfortunately, life in Turkey did not guarantee safety or hope for the future. Many people concealed their identities by taking on new official names and using pseudonyms in public. A large proportion of the 1.8 million Syrian refugees in Turkey currently live in camps that offer basic levels of shelter, food and healthcare. The majority of people I met, however, lived in urban areas without access to even these basic resources. Even within this context, people warmly welcomed me into their organizations and homes to share yoga. Yoga for Syrians A growing number of humanitarian agencies are discussing the need for conflict and post-conflict programs to incorporate ‘psychosocial services’ – a broad term used to encompass a range of activities that increase emotional resilience. In this case, Syrian health and civil society nonprofits were receptive to yoga as a psychosocial activity that promotes relaxation techniques. I collaborated with organizational representatives to discuss the context of classes, give presentations on the psychosocial benefits of yoga and schedule classes. Within this framework, I taught one to two yoga classes each day, each one lasting anywhere from 15 to 60 minutes. I offered daily classes to employees in a civil society organization, and periodic classes at youth schools and women’s clubs. Adult classes typically included four to ten participants per class whereas the classes in schools ranged from 20 to 50 students. The sequences consisted of breathing practices, guided relaxation and simple poses that could be done wearing normal attire. Over the course of a few weeks, I introduced participants to home practices and provided handouts in Arabic. Handouts for adults were short relaxation practices to address the most common ailments reported: back pain and difficulty sleeping. Children received copies of breathing practices (with a fun twist) that we did during class. Classes were positively received across organizations. Nonprofit employees reported better concentration in their offices after lunchtime yoga sessions. School teachers expressed amazement at how effectively the children learned to focus on their breath, and they enthusiastically asked for resources to continue yoga activities. Children shared that they not only enjoyed the take-home practices, but also shared them with siblings. Women described a weight being lifted from their chests when they completed breathing practices before bed. However, there were moments in several classes when the grief was so palpable that I had to pause and take a few deep breaths to ground myself while teaching. This sorrow was particularly salient when I was teaching a women’s group whose children had been abducted by Daesh. The walls where we practiced yoga were laminated with photos of smiling children, their names and ages inscribed at the bottom of each image. Their mothers were all from the same town and it was unlikely any of them would ever see their beloved children again. The feeling that was more substantial than grief was the social spirit that the Syrians brought into every yoga session. During classes, people would affectionately joke with one another about the challenges of the new activity. They playfully debated if yoga could cure conditions such as a smoker’s cough. After classes, participants were eager to keep spending time together. Women served cake and tea as they caught up on news about each other’s families and quizzed me enthusiastically about my family plans. Nonprofit workers organized post-yoga luncheons and city excursions where we discussed yoga philosophy. At the conclusion of their classes, children sang and performed dabke, an Arab tradition that consists of holding hands and dancing in a circle. The solace and joy they created and found in each other’s company was unmistakable. Community and Collective Healing Syrians in Turkey are seeking at least two avenues for healing. First, they are searching for ways to cope with their individual experiences of violence and loss. Second, they are processing a collective memory of painful events and injustices — all while striving to build new communities. Syrians are actively building support networks that reinforce the significance of collective healing after a collective trauma. In fact, a growing body of research on collective trauma emphasizes that psychological outcomes are more closely linked to social support than with an individual’s history of direct exposure to events like violence or torture. The World Health Organization even recommends large-scale programs to promote healing from trauma as a necessity to prevent further violence, and as a prerequisite to post-conflict reconciliation. Integrating yoga into programs for survivors of collective trauma is a relatively new type of intervention. In the U.S., the majority of trauma related programs (yoga and non-yoga) are modeled after a biomedical framework focused on the individual’s experience. The Syrians taught me the importance of moving beyond this structure so that yoga also fosters collective healing. In each of the settings where I taught, it was important to ensure yoga was part of and contributed to existing support mechanisms. Yoga simply represented an opportunity for a social activity that led to community discussion and goal setting. The social spirit that Syrians brought to our yoga sessions created an environment that nurtured resilience and healing — for them, and for their communities. Their sense of togetherness reminded me of a quote by my teacher, Mr. T. K. V. Desikachar, on the topic of faith and healing: “…the energy of togetherness is much more than the sum of individual energies” [1]. I hope that all of my future yoga classes vibrate with such a strong sense of togetherness, from Syria to my new home in Seattle. [1] Desikachar, T. K. V. and Martyn Neal (2001). What are we seeking? Krishnamacharya Yoga Mandiram, Chennai, India.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

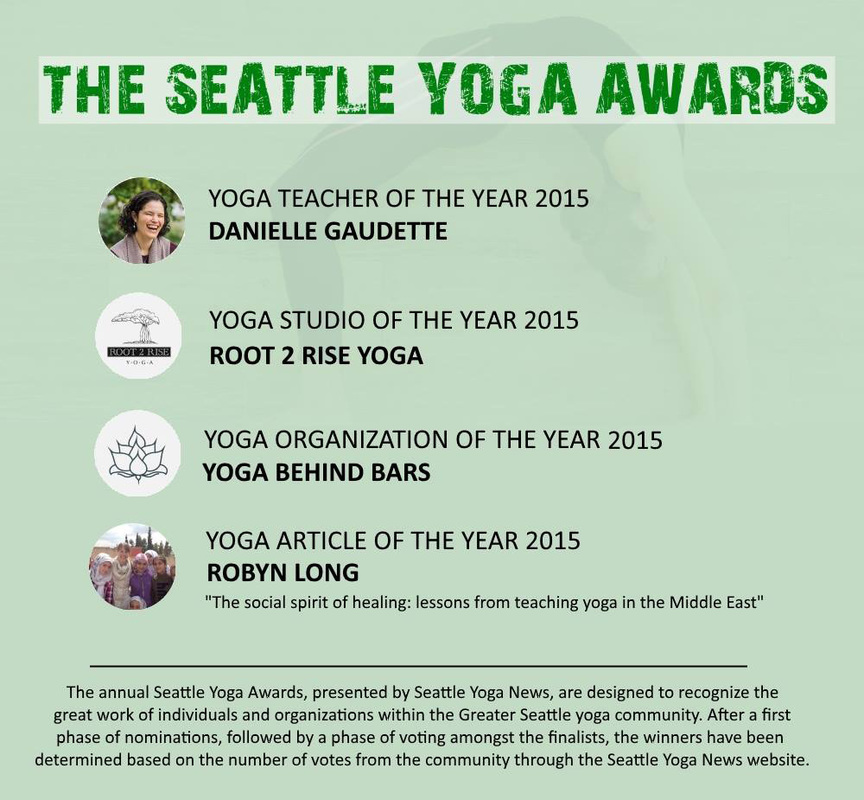

It is a tremendous honor that my article on sharing yoga with Syrians won "Yoga Article of the Year" in Seattle Yoga News. Endless gratitude to everyone who was part of and supported this inspiring project.

Archives

July 2017

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed