|

Every time I sit down to write a new post, there are a dozen things competing for my attention and time. Deadlines at work, outlining a new yoga class, or booking camp sites and researching family friendly hikes. The most adorable and important of things is my little yogi. I drop everything when he’s awake to play outside, read a book, or practice mama-baby yoga. Until he starts taking longer naps and I have more time for writing, here are a few snapshots of him working hard on his favorite yoga poses.

0 Comments

This article was originally published by Seattle Yoga News. The hustle and bustle of back-to-school has parents and children alike needing to pause and take a few deep breaths. Mindfulness, an awareness of the present moment with a kind and curious attitude, is a practice that benefits everyone in the family. A growing body of research is increasingly showing that mindfulness has a number of benefits for children such as increased self-regulation of emotions, behavior, and cognitive processes, as well as improved attention and executive function [1]. Emerging research has also explored how parent-child mindfulness programs enhance parent-youth relationships and improve children’s behaviors [2]. It’s easier than one thinks to share mindfulness as a family. Keeping it simple and fun are the two key aspects of a successful mindfulness activity with children. Here are three examples of ways to bring mindfulness into your and your child’s day. 1. Start with breath and body focused practices One of the simplest and most powerful practices in mindfulness is bringing attention to the breath. It is a tangible method that has demonstrated physiological changes such as activating the parasympathetic nervous system (i.e., the relaxation response). Yoga postures also help children learn to focus on the breath since they can link movement with breath (e.g., inhale and reach your arms up to the stars!). Cuing children to observe how they feel before, during, and after a pose is also an effective way to build self-awareness.

2. Engage the senses in everyday activities Children are naturally inclined to be in the moment and notice the world around them. An excellent way to encourage this awareness is through short mindful moments. Example: A mindful walk During a walk to school or the park, designate two minutes for each of the senses and observe the world around you through that lens. Share what each of you experienced in between each sensory observation.

3. Weave mindful reflections into daily routines Several of the foundational qualities to mindfulness can promote children’s social-emotional development (e.g., non-judgment, patience, curiosity, and compassion). Encouraging children to reflect on how they demonstrate these qualities towards themselves and others is an excellent way to support them in developing healthy emotional coping skills. Pick a time of day when you and your child can regularly take a few minutes to connect. This might be after school, at dinner, or before bed. Pick one or more mindfulness qualities to ask him about. Example: Mindful check-in

Interested in learning more? The Center for Child and Family Well-Being at the University of Washington hosts monthly Family Mindfulness Events. Children and their parents will explore mindfulness concepts through art and games, as well as learn simple practices they can take home. Check out details on the CCFW website or email Robyn Long, CCFW Director of Community Outreach and Dissemination, at [email protected]. References

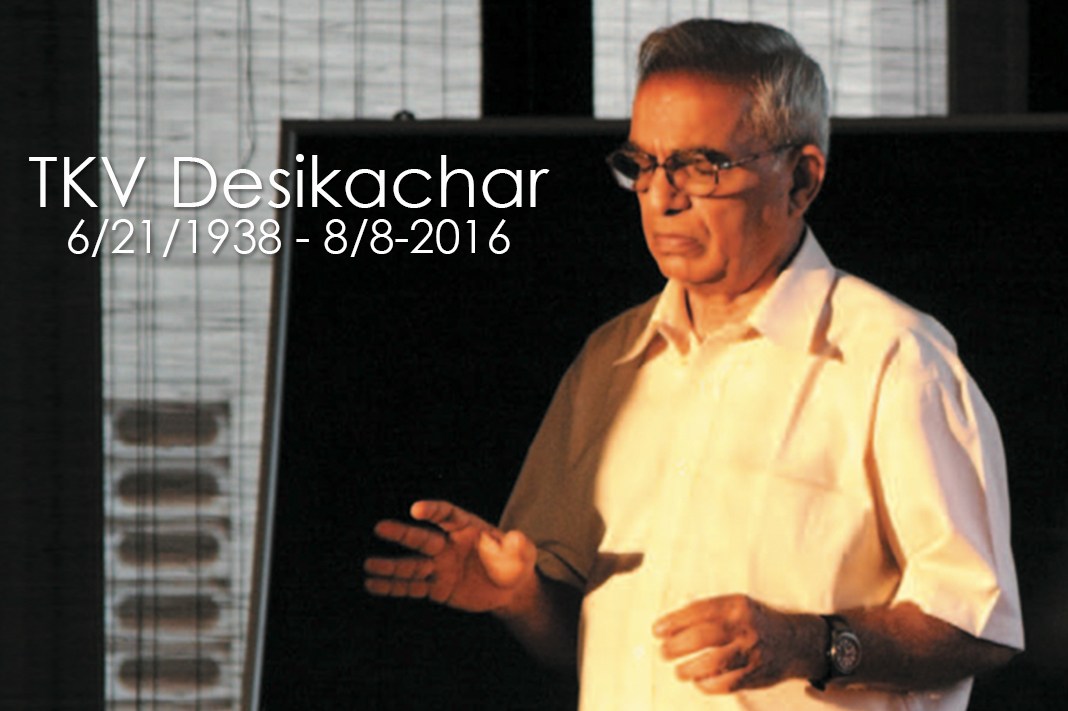

1 Perry-Parrish C, Copeland-Linder N, Webb L, Sibinga EMS. Mindfulness-based approaches for children and youth. Current Problems in Pediatric and Adolescent Health Care 2015; 46(6): 172 – 178. 2 Coatsworth JD, Duncan LG, Nix RL, et al. Integrating mindfulness with parent training: effects of the mindfulness enhanced strengthening families program. Developmental Psychology 2015; 51(1): 26-35. This article was originally published by Seattle Yoga News. I distinctly recall the feeling of the south Indian breeze (and humidity) flowing in and out of the Krishnamacharya Yoga Mandiram (KYM)’s windows on our first day of training. I was nervous, yet extremely excited, as twenty-five of us students from all corners of the globe sat eagerly awaiting Sir Desikachar. In line with tradition, we all stood to our feet when he entered the room. His presence was warm and welcoming. He took the time to look at each of us individually, then he asked each one of us to share what yoga meant to us. As we went around the room it was apparent that he was genuinely interested in how we each defined yoga for ourselves. It was our first lesson on pausing to reflect rather than searching for the “correct” answer. Over the next two and a half years and three trips to Chennai, my mind and heart were filled with his teachings. Forty years ago, Sir Desikachar founded KYM in Chennai, India, with a goal of sharing the wisdom and teachings of his father, Sri Tirumalai Krishnamacharya. Through KYM, he revived yoga’s ancient and powerful teachings while making them accessible and relevant to people from all cultures and traditions. As a graduate from KYM’s teacher training program, the following are a few of Sir Desikachar’s teachings that continue to guide my personal practice and work as a yoga instructor. Connect with the Power of the Breath “Anybody can breathe; therefore, anybody can practice yoga.” T. K. V. Desikachar [1] One of the defining aspects of yoga in the Krishnamacharya tradition is a strong emphasis on the breath in all aspects of practice. In fact, Sir Desikachar highlighted that linking the breath and body is the first step in yoga. This link is a tangible way to observe what is going on in the body and mind. To underscore this connection, he often cited the Hatha Yoga Pradipika, one of the oldest texts on Hatha yoga, “When the breath is disturbed, the mind is disturbed. When the breath is calm, the mind is calm.” On a subtler level, he emphasized that the quality of our breath is an expression of our inner most feelings. In our training, learning the patterns of our breath wasn’t a physiological exercise. It was a means to becoming aware about how we could shift our energetic states. The act of pausing to mindfully observe the breath is a simple way to develop a more intimate awareness with oneself in yoga. Ensure Yoga’s Accessibility to All “It is not that the person needs to accommodate him or herself to yoga, but rather the yoga practice must be tailored to fit each person.” T. K. V. Desikachar [1] Sir Desikachar carried out his father’s legacy of adapting yoga to the unique needs of each individual. This is a profound and liberating concept as a yoga practioner and instructor. In a personal practice, this requires one to be mindful and reflect on what is needed in that day and in that moment. In a teaching context, Sir Desikachar noted that one should consider each person’s background and culture as well as their physical, emotional, and mental states – all of which change from day to day. One of the greatest lessons I learned at KYM (and continue to learn) was how to cultivate this atmosphere in a group class. For example, one strategy is to offer participants one or two modifications of a posture or breathing practice, provide them with a mindful pause, and invite them to reflect on what they need in that moment. One of Sir Desikachar’s pillars to ensuring yoga is accessible to people from all walks of life was by inviting transformation instead of simply giving someone information and expecting them to absorb it. In one lecture, he spoke about the importance of honoring each individual’s path in yoga. I remember how he would often pause after talking and scan the room – he wanted to ensure we understood his message. We were discussing how to incorporate yoga’s subtler elements, such as meditation, when most people came to class for the postures. He emphasized that this is their path in healing and transformation. It was the teacher’s responsibility to honor that path while creating a space where students could explore other aspects of yoga further. Live and Practice Yoga from the Heart “The success of Yoga does not lie in the ability to perform postures but in how it positively changes the way we live our life and our relationships.” T. K. V. Desikachar One of Sir Desikachar’s definitions of yoga was “an awareness of and positive attitude towards what is happening within and outside of oneself”. His teachings encouraged people to look within themselves – into the heart, where he noted our true nature resides. In one lecture on meditation, he spoke to how we rarely take the time in our busy lives to actually listen to our feelings. Sir described meditation as an opportunity to reconnect with ourselves, “open the door to our own hearts”, and listen to what was happening deep within ourselves. Classes in the tradition of Krishnamacharya are thoughtfully sequenced to offer students tools for connecting with the heart. Of all the practices Sir Desikachar taught, the ones that I found most moving used nyasa, a technique where one touches a specific point on the body while chanting a mantra. For example, on the inhalation he would instruct us to stretch our arms open to the sides, and on the exhalation to chant “Aum” while placing our palms over our heart. There are infinite possibilities of mantras and energetic points one could use – adding to the richness of Sir Desikachar’s teachings. The use of mantra and nyasa in this way is a powerful means to deepen my own practice, and a tool that I consistently rely on when teaching. His Light & Legacy Sir Desikachar is a profound example of what it means to live and follow the path of yoga. I was always moved by his welcoming demeanor; he greeted and listened to everyone without judgement. Through his institute and travels worldwide, he positively touched the lives of thousands seeking healing through yoga. While our teacher has passed on from this world, Sir’s spirit and teachings remain alive, not only through his students, but through the cultural impact he has had in redefining the fields of yoga and yoga therapy. He will be deeply missed and remembered as one of the most influential teachers and masters of yoga. Resources:

[1] Desikachar, T. K. V. (1999). The Heart of Yoga: Developing a Personal Practice. Rochester, VT. Inner Traditions. [Photos from KYM.org] Other books by Sir Desikachar: Desikachar, T. K. V. and Neal, M. (2001). What are we seeking? Chennai, India. Krishnamacharya Yoga Mandiram. Desikachar, T. K. V. and Cravens, R. H. (2011). Health, Healing, and Beyond. Yoga and the Living Tradition of T. Krishnamacharya KYM has several apps to support study of the Yoga Sutras and chanting. Visit the KYM website for details. This article originally appeared in Seattle Yoga News.

This summer, the Center for Child and Family Well-Being (CCFW) at the University of Washington (UW) is piloting a mindfulness-childbirth education program for pregnant women who have experienced sexual abuse or assault. We talked with CCFW staff and the study’s interdisciplinary team to learn more about this research. Joining us for the discussion is:

The mindfulness-childbirth education study will explore how providing support to women through self-care strategies can help them manage stress in times of potential adversity. This is an important research area since women who have experienced sexual trauma might experience additional challenges such as distress and depression during their pregnancy and after their give birth to their babies. Research shows that parental stress can play a role in children’s social, emotional, and behavioral adjustment. This study looks at how to improve the well-being of mothers-to-be, which can in turn improve health outcomes for their children. Q2: Can you share an overview of the study’s objectives and protocol? What brought your team together to embark on this research?Cynthia: This study is designed to provide pregnant women with a history of sexual trauma with mindfulness skills within the context of a childbirth education program, to help support them as they prepare for delivery and parenting. “Mindfulness-Based Childbirth and Parenting” (MBCP) is a program developed by midwife Nancy Bardacke. The objective of this study is to examine the feasibility and acceptability of a modified trauma-informed approach to mindfulness for childbirth education. To examine feasibility and acceptability we’ll ask participants for their feedback related to the class structure and content. We will also look at their responses to self-report health questionnaires related to anxiety, depression and coping skills to provide insight on the potential benefits of the program. This study begins in mid-June so we’re seeking study volunteers now! Q3: How will you bring mindfulness into childbirth education? Can you give an example of something participants might learn?Becca: The foundation of this class are mindfulness skills, which are taught through practices such as awareness of breathing meditation, mindful eating, and mindful movement (e.g. gentle yoga and walking meditation). Using this lens of mindfulness, we discuss topics covered in typical childbirth education classes including: the stages of labor, positions for ease in labor, skills for coping with pain and fear, and suggestions for communicating well with providers. In these discussions, special attention is paid to how being aware of one’s present moment experience – sensations, thoughts, emotions – can support a sense of ease even when facing the challenges of childbirth. By bringing present moment awareness to the realm of childbirth, women are able to see their expectations, hopes and fears more clearly. This allows them to develop plans for support and coping that speak directly to their own experiences. After taking the MBCP class, many students report feeling more calm and confident that they have the skills to cope well with labor and early parenting, however it may unfold for them. Q4: What are some of the adaptations you’ve made to make the mindfulness program supportive to women with a history of sexual trauma? Cynthia: We have expanded the program to include three coaching sessions, delivered individually vs. in a group, to focus on mindful body awareness. Women with histories of sexual trauma can find it challenging to connect to their bodies because many of the coping strategies for trauma involve avoidance of bodily sensations. Attending to sensations in the body (e.g. breath) is integral to mindfulness. The one-on-one sessions are designed to provide individualized coaching to facilitate learning how to bring mindful attention into the body, to practice this in daily life, and to use in response to stressful situations to facilitate regulation. In addition, the childbirth education classes will include more explicit discussion of how to prepare and cope with anxieties related to delivery and parenting that may stem from past traumatic experiences. Q5: How might mindfulness skills support women during labor? Ira: Labor and birth are intense experiences that involve physical sensations, strong emotions, and intimacy. Even under ideal circumstances the maelstrom of sensations can be overwhelming. Women with histories of sexual abuse or trauma may fear the childbirth experience because it may trigger memories of their abuse. I have cared for women who would rather give birth by cesarean than face these sensations. Mindfulness skills have the potential to help women face the physical sensations and the emotions they evoke without feeling overwhelmed. This has the potential for turning the labor and birth into an empowering and life-changing experience which allows them to develop an improved relationship with their physical bodies. Q6: How will you involve participants’ support persons? Why is it important to engage them in this program?Becca: Support people are encouraged to attend and will be invited to fully participate in class activities and discussions along with the pregnant women. There are exercises in the class which focus specifically on teaching hands on support techniques that can be helpful in labor and opportunities for the pregnant women to share which techniques work well for them. Opening this communication for the women to share what is helpful and what is not lays the ground work for supportive communication during the birth process. In addition to being valuable for labor and birth, the mindfulness skills that are taught are useful for coping with many aspects of life – work stress, family and relationship challenges, and changes associated with having a baby. Support people often find the class teachings to be valuable over and above what it offers to them in their role as birth support. Q7: How much research has already been done in this specific field?Cynthia: To our knowledge there has been no prior research on mindfulness in childbirth education for women with trauma histories. There is considerable research evidence that a history of sexual trauma is a risk factor for prenatal anxiety and depression, putting women at risk for post-partum depression and poorer maternal and child health [1, 2]. Research studies also show that anxiety and depression can be improved during pregnancy and that such improvement may have a positive impact on obstetric outcomes as well as maternal and child health [2]. There is substantial research to show that mindfulness interventions reduce anxiety and depression [3]; mindfulness studies for pregnant women also shows reductions in anxiety and depression but with fewer studies to clearly show efficacy [4]. Together the research in these areas suggests that providing mindfulness skills for pregnant women who have a trauma history may be a useful approach to improve obstetric, maternal and child health. Q8: How might findings from this research lead to improved care for women during labor? Ira: Helping laboring women stay focused on the present can reduce the fear of childbirth and emotional pain of past memories of abuse. Staying mindful during the minutes between contractions allows the woman to take advantage of the natural rest periods during labor to rejuvenate and conserve strength for the next contraction. Our research has the potential to show that the mindfulness approach can help women with histories of sexual trauma and catalyze a positive relationship with her embodied sensations. Even if a woman chooses not to share her history of sexual abuse with her provider, she may find the mindfulness skills helpful as she focuses inward during labor and birth. When she does share her past history of abuse, the provider can facilitate her journey through providing an environment that supports the mindfulness approach. This can include reducing the distractions in the labor and birth room and gently reminding the laboring woman to remain focused on the present. Q9: How will this study contribute to future research and programs at CCFW?Robyn: This study addresses a gap between mindfulness, prenatal care, and trauma research. The research team brings together an incredible amount of knowledge and practice experience in these fields. They are well poised to adapt and assess a mindfulness program for women during this important period of life. This research will provide CCFW with information and insights necessary to embark on a larger study that explores how to effectively support women with a history of trauma during and after pregnancy. Ultimately, we anticipate that this research will have implications for trauma-informed mindfulness programs as well as prenatal care. More Information Interested in participating in the study? Contact Anna Treadway, Research Coordinator, at 206.616.6423 [email protected]. Interested in more information about the Center for Child and Family Well-Being? Visit our website at www.depts.washington.edu/ccfwb or email Robyn at [email protected]. References 1. Yim, I., Stapleton, L, Guardino, C., Hahn-Holbrook, J., Schetter, C. 2015. Biolobical and Psychosocial Predictors of Postpartum Depression: Systematic Review and Call for Integration. The Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 11: 99-137. 2. Martini, J., Petzoldt, J., Einsle, F., Beesdo-Baum, K., Hofler, M., Wittchen, H. 2015. Risk Factors and course patterns of anxiety and depressive disorders during pregnancy and after delivery: A prospective-longitudinal study. Journal of Affective Disorders, 175: 385-395. 3. Gu J, Strauss C, Bond R, Cavanagh K. How do mindfulness-based cognitive therapy and mindfulness based stress reduction improve mental health and wellbeing? A systematic review and meta-analysis of mediation studies. Clinical Psychology Review. 2015; 37(1–12). 4. Taylor, B., Cavanaugh, K., Strauss, C. (2016). The Effectiveness of Mindfulness-Based Interventions in the Perinatal Period: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. PLOSone, 11 (5): e0155720. |

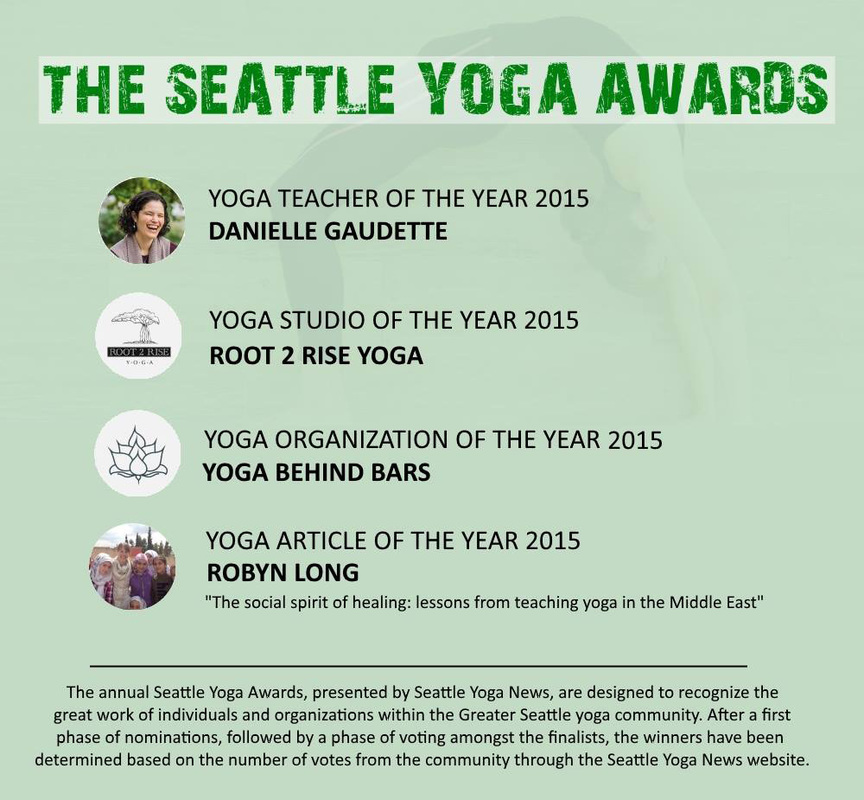

It is a tremendous honor that my article on sharing yoga with Syrians won "Yoga Article of the Year" in Seattle Yoga News. Endless gratitude to everyone who was part of and supported this inspiring project.

Archives

July 2017

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed