|

One of the aspects of yoga that I’m most drawn to is the concept of seva, a Sanskrit term that refers to selfless service. Seva is considered to be a core aspect of personal growth and transformation in the path of yoga. The ancient yoga gurus believed that practicing seva enables us to attain a deeper understanding of ourselves and, as a result, attain a higher level of consciousness.

Two pillars of seva are compassion and promoting collective wellbeing. There are dozens of ways that we can practice seva on a daily basis – everything from random acts of kindness to volunteering with a community organization, or spending quality time with your family. What is most important in selecting activities is that:

Anyone who has volunteered for a cause they are passionate about knows the power of giving your time and energy – it is inspiring, humbling, and often a lot of fun! To foster the exchange of ideas about practicing seva, I’m starting a series of #sevasaturday posts. Keep watch for ideas and share your seva activities to inspire more action.

0 Comments

This is the first of several posts that are based on my experience sharing yoga with Syrians who have sought safety and refuge in Turkey. In Gaziantep and Sanliurfa, two cities now home to approximately 500,000 Syrians each, I taught yoga classes for civil society groups, women’s clubs, and schools in the spring of 2015.

In my global travels, I have become increasingly attentive to the different meanings “yoga” has for people from diverse religious, social, and cultural backgrounds. I have taught yoga within the walls of churches in Canada, and the circles of Islamic societies in the Middle East. My most recent experience teaching yoga within Syrian communities reinforces the importance of focusing on the essence of yoga as service by ensuring that it is accessible in an array of cultural contexts. I wear two hats when developing community yoga programs. The first hat is that of a grassroots international development practitioner. This involves collaborating with partner organizations to brainstorm and evaluate the best approaches to tailor a program so that it is meaningful to participants, and accepted by their communities. The second hat that I wear is that of a yoga teacher and student within the tradition of Sri Krishnamacharya. Sri Krishnamacharya’s son, Mr. T.K.V. Desikachar, my teacher and founder of theKrishnamacharya Yoga Mandiram (KYM) in India, has dedicated his life to ensuring yoga is accessible and relevant to people from all corners of the globe. During our training, Mr. Desikachar and the KYM faculty often challenged us to assess whether a certain activity or action was or was not “yoga”. In the end, the conclusion that we always came to was not defining yoga by a style or set of postures but instead understanding yoga as a form of service [1]. Naming and Explaining Yoga Prior to embarking on my work with Syrian organizations, I decided to use the term yoga for classes. My decision was based on previous experiences teaching yoga in Palestine, where the term was accepted. Over the last few years, there has also been an emergence of yoga studios throughout the Middle East. Once I began, one Syrian organization openly welcomed yoga and we had classes almost daily. Unfortunately, I did encounter resistance to yoga within other organizations. The European director of a school for Syrian children, supported by a European-Christian association, canceled yoga classes under the suspicion that yoga may contradict their faith. I was unsuccessful in reinstating those classes despite my best efforts in clarifying that yoga was not religious or even linked to Hinduism (as a note, Hinduism rejected yoga as a school of thought in India because the ancient yoga texts do not insist that God exists). Disappointed by the cancellation of yoga in one school, I recognized that yoga might not be an appropriate term for all organizations. What then, should classes be called? I reflected on what I had learned during my teacher training at KYM. In therapeutic contexts, yoga is a holistic, individualized practice to improve wellbeing. It offers approaches to healing by bringing the mind to stillness and reducing suffering through a strengthened relationship with oneself. In fact, Mr. Desikachar has described yoga as “a relationship with our own self”. In the tradition of Krishnamacharya, we employ a variety of practical tools (e.g., postures, breathing, meditation, mantra) that empower participants to take action in their own health and healing. After consulting with contacts from Syrian organizations, I decided that it would be best to start using language that reflected the tools employed in class and that resonated with the organization’s services. I described classes as opportunities for participants to focus on themselves and learn relaxation skills such as breathing techniques. This explanation aligned with the growing emphasis on psychosocial programming by Syrian groups. After some simple wording adjustments, sessions were welcomed in a range of settings including other schools and nonprofit organizations. The following are two examples of how language was adapted. Sessions for children were held during physical education (P.E.) class and called “exercise and relaxation”. In advance of classes, I developed a set of cards with images of postures and breathing practices in Arabic (see images below). When I met with directors and teachers, I shared the cards and explained that the progression of a class moved from active postures into guided breathing while sitting or lying down. After classes, teachers remarked that the cards were engaging and fun for students and that the sequence was effective in leading them into relaxation. They also shared that the cards were useful resources in continuing the classes after my volunteer time ended. In addition, I named the adult classes “relaxation practices”. Prior to starting classes, I gave a presentation for organizational representatives that outlined the class format and highlighted how relaxation practices, such as breathing techniques, connect to the nervous system and benefit people who have experienced traumatic events. During classes, I selected postures that would be easy to learn, comfortable to do in regular clothing, and safe to practice at home without props. Coincidentally, several of the postures corresponded to the movements performed in the Muslim prayer. This was only partially intentional because some of these yoga postures are frequently used in therapeutic settings (e.g., Uttanasana and Cakravakasana, which are similar to the Muslim prayer movements of Ruku and Sujud). Participants approvingly remarked on this similarity and shared that it made learning some of the movements less intimidating. In terms of language used during classes, I did not use any Sanskrit terms – something commonly done in yoga. I named postures and breathing practices in children’s classes after animals and shapes. Several Syrian representatives in partner organizations vetted the names to ensure that they were culturally appropriate. In adult classes I simply described the movement, e.g., “arm raises” and “forward bend”. In a few instances, participants did ask me “Is this similar to yoga?” I responded that yes, many would call it yoga, including myself if I were teaching back home. I also shared that I had studied yoga, as well as other forms of mindfulness and relaxation, in India, Canada, and the US. Though my experience was confined to a few weeks, this discussion never had negative outcomes. In fact, it led to further discussions on the differences between various mind-body programs. At that point, I asked people what they would prefer classes be called; the consensus was always to keep the name as it was (i.e., not yoga) given potential sensitivities that conservative religious groups might have. Focusing on Service In the spirit of yoga as service, it was important to let go of my labels and definitions of yoga. While I am adamant that “exercise” is not “yoga”, exercise was the appropriate term to use in conjunction with relaxation for the children’s classes. As Mr. Desikachar noted, “...there are many possible ways of understanding the meaning of the word yoga. Yoga has its roots in Indian thought, but its content is universal because it is about the means by which we can make the changes we desire in our lives. The actual practice of yoga takes each person in a different direction” [2]. Just as the practice for each person is different, so is the most appropriate approach to offering programs in different cultural settings. As a yoga teacher, I strive to teach to the needs of participants in my class on that day, in that moment. I am grateful to have learned more about the art of adapting classes beyond the physical postures and breathing practices, but also my language and approaches to partnering with diverse organizations. These adaptations ensure the programs were accessible and welcomed by an array of community groups. [1] Mr. Desikachar discussed the importance of not defining yoga by style but instead as a service in an interview on Yoga Chicago. [2] The Heart of Yoga: Developing a Personal Practice, T. K. V. Desikachar, 1999. Top image: Gaziantep, Turkey, Photo © 2015 Robyn B. Long |

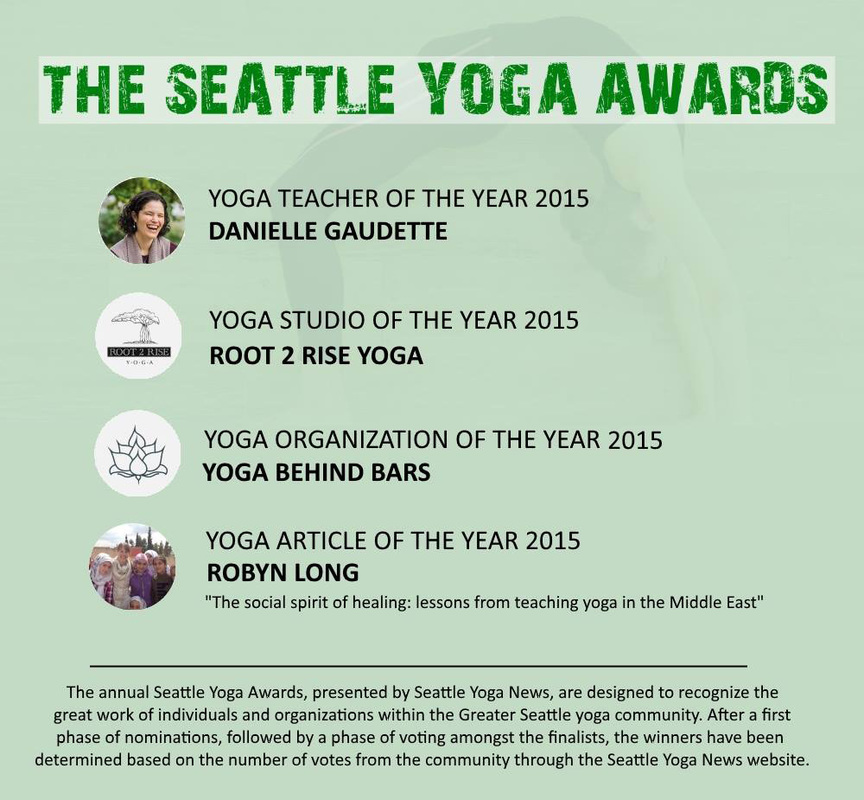

It is a tremendous honor that my article on sharing yoga with Syrians won "Yoga Article of the Year" in Seattle Yoga News. Endless gratitude to everyone who was part of and supported this inspiring project.

Archives

July 2017

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed