|

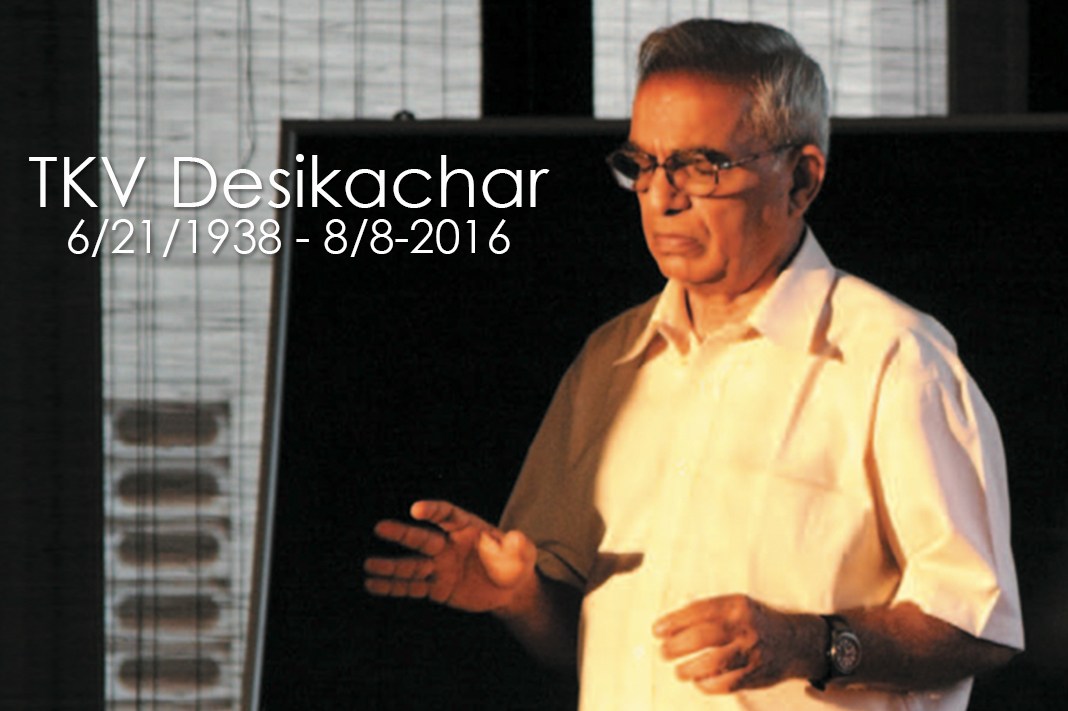

This article was originally published by Seattle Yoga News. I distinctly recall the feeling of the south Indian breeze (and humidity) flowing in and out of the Krishnamacharya Yoga Mandiram (KYM)’s windows on our first day of training. I was nervous, yet extremely excited, as twenty-five of us students from all corners of the globe sat eagerly awaiting Sir Desikachar. In line with tradition, we all stood to our feet when he entered the room. His presence was warm and welcoming. He took the time to look at each of us individually, then he asked each one of us to share what yoga meant to us. As we went around the room it was apparent that he was genuinely interested in how we each defined yoga for ourselves. It was our first lesson on pausing to reflect rather than searching for the “correct” answer. Over the next two and a half years and three trips to Chennai, my mind and heart were filled with his teachings. Forty years ago, Sir Desikachar founded KYM in Chennai, India, with a goal of sharing the wisdom and teachings of his father, Sri Tirumalai Krishnamacharya. Through KYM, he revived yoga’s ancient and powerful teachings while making them accessible and relevant to people from all cultures and traditions. As a graduate from KYM’s teacher training program, the following are a few of Sir Desikachar’s teachings that continue to guide my personal practice and work as a yoga instructor. Connect with the Power of the Breath “Anybody can breathe; therefore, anybody can practice yoga.” T. K. V. Desikachar [1] One of the defining aspects of yoga in the Krishnamacharya tradition is a strong emphasis on the breath in all aspects of practice. In fact, Sir Desikachar highlighted that linking the breath and body is the first step in yoga. This link is a tangible way to observe what is going on in the body and mind. To underscore this connection, he often cited the Hatha Yoga Pradipika, one of the oldest texts on Hatha yoga, “When the breath is disturbed, the mind is disturbed. When the breath is calm, the mind is calm.” On a subtler level, he emphasized that the quality of our breath is an expression of our inner most feelings. In our training, learning the patterns of our breath wasn’t a physiological exercise. It was a means to becoming aware about how we could shift our energetic states. The act of pausing to mindfully observe the breath is a simple way to develop a more intimate awareness with oneself in yoga. Ensure Yoga’s Accessibility to All “It is not that the person needs to accommodate him or herself to yoga, but rather the yoga practice must be tailored to fit each person.” T. K. V. Desikachar [1] Sir Desikachar carried out his father’s legacy of adapting yoga to the unique needs of each individual. This is a profound and liberating concept as a yoga practioner and instructor. In a personal practice, this requires one to be mindful and reflect on what is needed in that day and in that moment. In a teaching context, Sir Desikachar noted that one should consider each person’s background and culture as well as their physical, emotional, and mental states – all of which change from day to day. One of the greatest lessons I learned at KYM (and continue to learn) was how to cultivate this atmosphere in a group class. For example, one strategy is to offer participants one or two modifications of a posture or breathing practice, provide them with a mindful pause, and invite them to reflect on what they need in that moment. One of Sir Desikachar’s pillars to ensuring yoga is accessible to people from all walks of life was by inviting transformation instead of simply giving someone information and expecting them to absorb it. In one lecture, he spoke about the importance of honoring each individual’s path in yoga. I remember how he would often pause after talking and scan the room – he wanted to ensure we understood his message. We were discussing how to incorporate yoga’s subtler elements, such as meditation, when most people came to class for the postures. He emphasized that this is their path in healing and transformation. It was the teacher’s responsibility to honor that path while creating a space where students could explore other aspects of yoga further. Live and Practice Yoga from the Heart “The success of Yoga does not lie in the ability to perform postures but in how it positively changes the way we live our life and our relationships.” T. K. V. Desikachar One of Sir Desikachar’s definitions of yoga was “an awareness of and positive attitude towards what is happening within and outside of oneself”. His teachings encouraged people to look within themselves – into the heart, where he noted our true nature resides. In one lecture on meditation, he spoke to how we rarely take the time in our busy lives to actually listen to our feelings. Sir described meditation as an opportunity to reconnect with ourselves, “open the door to our own hearts”, and listen to what was happening deep within ourselves. Classes in the tradition of Krishnamacharya are thoughtfully sequenced to offer students tools for connecting with the heart. Of all the practices Sir Desikachar taught, the ones that I found most moving used nyasa, a technique where one touches a specific point on the body while chanting a mantra. For example, on the inhalation he would instruct us to stretch our arms open to the sides, and on the exhalation to chant “Aum” while placing our palms over our heart. There are infinite possibilities of mantras and energetic points one could use – adding to the richness of Sir Desikachar’s teachings. The use of mantra and nyasa in this way is a powerful means to deepen my own practice, and a tool that I consistently rely on when teaching. His Light & Legacy Sir Desikachar is a profound example of what it means to live and follow the path of yoga. I was always moved by his welcoming demeanor; he greeted and listened to everyone without judgement. Through his institute and travels worldwide, he positively touched the lives of thousands seeking healing through yoga. While our teacher has passed on from this world, Sir’s spirit and teachings remain alive, not only through his students, but through the cultural impact he has had in redefining the fields of yoga and yoga therapy. He will be deeply missed and remembered as one of the most influential teachers and masters of yoga. Resources:

[1] Desikachar, T. K. V. (1999). The Heart of Yoga: Developing a Personal Practice. Rochester, VT. Inner Traditions. [Photos from KYM.org] Other books by Sir Desikachar: Desikachar, T. K. V. and Neal, M. (2001). What are we seeking? Chennai, India. Krishnamacharya Yoga Mandiram. Desikachar, T. K. V. and Cravens, R. H. (2011). Health, Healing, and Beyond. Yoga and the Living Tradition of T. Krishnamacharya KYM has several apps to support study of the Yoga Sutras and chanting. Visit the KYM website for details.

0 Comments

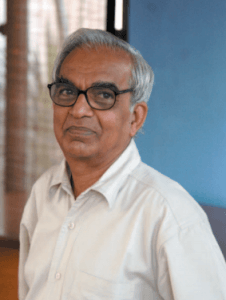

This article was originally featured on Seattle Yoga News, May 27, 2015. I spent this spring sharing yoga with Syrians seeking safety and refuge in southeast Turkey. I arrived well versed on the four-year Syrian crisis, prepared to teach yoga in Arabic and ready to be of service to people as they healed the wounds of conflict. When I arrived, the crisis was entering its fifth year and more than 220,000 Syrians had lost their lives. The news was always grim. Grief, distress and heartache were omnipresent when I arrived. But the most tangible sentiment I perceived was the sense of support and community that the Syrians brought to each yoga session. After only a few weeks of sharing yoga in local organizations, it became clear that their social spirit was their strongest source for healing. Yoga became a unique opportunity for them to connect with each other as they coped with distress from the crisis. Life in Turkey The Syrians who participated in my yoga classes had all endured immeasurable loss and survived harrowing circumstances. Many had watched in terror as their towns had been bombed or raided while their loved ones were imprisoned, executed or abducted. Many had fled after being targeted by the Syrian regime or extremist groups such as Daesh (the Arabic name for the Islamic State). The crisis disrupted all aspects of their lives; they were forced to postpone marriages, close family businesses and withdraw from university studies. The crisis unraveled the social fabric of everyday life; families were torn apart and communities were polarized by new religious and ethnic lines. One participant shared that her husband was en route to seek asylum in another country — a dangerous journey — and she had not heard from him in one month. Unfortunately, life in Turkey did not guarantee safety or hope for the future. Many people concealed their identities by taking on new official names and using pseudonyms in public. A large proportion of the 1.8 million Syrian refugees in Turkey currently live in camps that offer basic levels of shelter, food and healthcare. The majority of people I met, however, lived in urban areas without access to even these basic resources. Even within this context, people warmly welcomed me into their organizations and homes to share yoga. Yoga for Syrians A growing number of humanitarian agencies are discussing the need for conflict and post-conflict programs to incorporate ‘psychosocial services’ – a broad term used to encompass a range of activities that increase emotional resilience. In this case, Syrian health and civil society nonprofits were receptive to yoga as a psychosocial activity that promotes relaxation techniques. I collaborated with organizational representatives to discuss the context of classes, give presentations on the psychosocial benefits of yoga and schedule classes. Within this framework, I taught one to two yoga classes each day, each one lasting anywhere from 15 to 60 minutes. I offered daily classes to employees in a civil society organization, and periodic classes at youth schools and women’s clubs. Adult classes typically included four to ten participants per class whereas the classes in schools ranged from 20 to 50 students. The sequences consisted of breathing practices, guided relaxation and simple poses that could be done wearing normal attire. Over the course of a few weeks, I introduced participants to home practices and provided handouts in Arabic. Handouts for adults were short relaxation practices to address the most common ailments reported: back pain and difficulty sleeping. Children received copies of breathing practices (with a fun twist) that we did during class. Classes were positively received across organizations. Nonprofit employees reported better concentration in their offices after lunchtime yoga sessions. School teachers expressed amazement at how effectively the children learned to focus on their breath, and they enthusiastically asked for resources to continue yoga activities. Children shared that they not only enjoyed the take-home practices, but also shared them with siblings. Women described a weight being lifted from their chests when they completed breathing practices before bed. However, there were moments in several classes when the grief was so palpable that I had to pause and take a few deep breaths to ground myself while teaching. This sorrow was particularly salient when I was teaching a women’s group whose children had been abducted by Daesh. The walls where we practiced yoga were laminated with photos of smiling children, their names and ages inscribed at the bottom of each image. Their mothers were all from the same town and it was unlikely any of them would ever see their beloved children again. The feeling that was more substantial than grief was the social spirit that the Syrians brought into every yoga session. During classes, people would affectionately joke with one another about the challenges of the new activity. They playfully debated if yoga could cure conditions such as a smoker’s cough. After classes, participants were eager to keep spending time together. Women served cake and tea as they caught up on news about each other’s families and quizzed me enthusiastically about my family plans. Nonprofit workers organized post-yoga luncheons and city excursions where we discussed yoga philosophy. At the conclusion of their classes, children sang and performed dabke, an Arab tradition that consists of holding hands and dancing in a circle. The solace and joy they created and found in each other’s company was unmistakable. Community and Collective Healing Syrians in Turkey are seeking at least two avenues for healing. First, they are searching for ways to cope with their individual experiences of violence and loss. Second, they are processing a collective memory of painful events and injustices — all while striving to build new communities. Syrians are actively building support networks that reinforce the significance of collective healing after a collective trauma. In fact, a growing body of research on collective trauma emphasizes that psychological outcomes are more closely linked to social support than with an individual’s history of direct exposure to events like violence or torture. The World Health Organization even recommends large-scale programs to promote healing from trauma as a necessity to prevent further violence, and as a prerequisite to post-conflict reconciliation. Integrating yoga into programs for survivors of collective trauma is a relatively new type of intervention. In the U.S., the majority of trauma related programs (yoga and non-yoga) are modeled after a biomedical framework focused on the individual’s experience. The Syrians taught me the importance of moving beyond this structure so that yoga also fosters collective healing. In each of the settings where I taught, it was important to ensure yoga was part of and contributed to existing support mechanisms. Yoga simply represented an opportunity for a social activity that led to community discussion and goal setting. The social spirit that Syrians brought to our yoga sessions created an environment that nurtured resilience and healing — for them, and for their communities. Their sense of togetherness reminded me of a quote by my teacher, Mr. T. K. V. Desikachar, on the topic of faith and healing: “…the energy of togetherness is much more than the sum of individual energies” [1]. I hope that all of my future yoga classes vibrate with such a strong sense of togetherness, from Syria to my new home in Seattle. [1] Desikachar, T. K. V. and Martyn Neal (2001). What are we seeking? Krishnamacharya Yoga Mandiram, Chennai, India. Robyn Long with Josie Shagwert* This post is based on my experience sharing yoga with Syrians who have sought safety and refuge in Turkey. In Gaziantep and Şanliurfa, two cities now home to approximately 500,000 Syrians each, I taught yoga classes for civil society groups, women’s clubs, and schools in the spring of 2015. I am honored that my co-author Josie Shagwert has contributed her insight on the experiences of community development and life in exile as a member of a civil society organization promoting peace and democracy in Syria.

Yoga is a mindful activity that supports the interrelated physical, social, and emotional needs of people who have experienced traumatic events, such as war, displacement, and resettlement. Yoga practices offer survivors of such events an opportunity to experience relaxation and a sense of peace within themselves. Also, through yoga, participants have an opportunity to learn tools, such as breathing practices, which they can draw upon to address post-traumatic stress symptoms, such as an accelerated heartbeat or difficulty sleeping. Our experience in yoga programs for Syrians displaced by war offers insight and lessons for future programs and instructors in similar contexts. Namely, in communities displaced by conflict and violence, yoga programs focused on healing must be linked with existing networks and culturally-rooted practices. These networks and practices, formal and informal, are powerful resources for support and provide a sense of normalcy as people adjust to life in a new country. In yoga programs tailored for survivors of trauma and grief, teachers often discuss the art of “holding space” for participants. The concept of holding space spans the physical setting (e.g., how to arrange the yoga mats) to the emotional environment (e.g., how we foster a compassionate, stable, and non-judgmental atmosphere for participants to work through their experiences). The emphasis in these contexts is usually on the individual. For example, an instructor may provide ten minutes at the end of a class for relaxation, perhaps with a guided visualization or breathing practice. Afterwards, the teacher would be available for participants to discuss any emotions that surfaced or their experiences during the practice. When offering yoga to communities displaced by war, our recent experience suggests that yoga instructors should shift their focus of holding space from the individual to the group level. In fact, we found that it was critical for the instructor to be part of and contribute to the collective space that communities had already created. This sometimes meant discarding static notions of the “best” ways to practice in favor of adapting to the local atmosphere and practices, including making space for conversation and comments during class and doing traditional dances afterward. By adapting in these ways, both the instructor and the yoga experience gain more traction, trust and legitimacy in these settings – and thus are able to more fully contribute to healing for the participants. Yoga for Syrian communities in exile Syrians who have sought safety in Turkey face an array of daily challenges. Turkey is host to the largest number of Syrian refugees, with nearly 1.8 million registered in the country [1]. Many of the refugees live in camps that provide at least basic levels of food, shelter, and healthcare. Many, however, live outside of the camps and lack access to healthcare, stable shelter, employment, etc. Very few speak the local language fluently and nearly everyone has to adapt to new living arrangements and assume increased family responsibilities. Each person has a harrowing story of escape and has lost or been separated from loved ones. People are simultaneously building a new community while striving to promote stability in their homeland. In this context, they have formed support networks in everyday environments such as work, school, and informal social settings. To promote the wellbeing of Syrians in this context, we offered yoga in a range of group settings, such as the workplace, women’s clubs, and schools. Yoga was welcomed by multiple groups as an activity for people to learn skills for relaxation and healing. Several basic considerations were taken into account when designing the classes:

1. Integrate traditional social activities into yoga Social activities are a critical aspect of community building in Syrian culture. For example, after a club meeting, women typically converse over tea and snacks. In a school setting, children often sing and perform dabke, an Arab tradition that consists in dancing in a circle while holding hands. These collective activities are particularly important for Syrians displaced by war because they promote a sense of solace as a familiar activity from home. Creating time for social activities after yoga provides a grounding activity for participants after individual relaxation and reflection. In our experience, the activities happened organically and they brought participants together to support one another – which was beneficial as new emotions can surface during or after yoga. It was also during these activities that participants expressed the impact yoga had for them. For example, it was in a circle while dancing dabke that girls at school remarked on how yoga made them feel energized, relaxed, or “free to breathe”. 2. Remain flexible to the time and needs of organizations Yoga that takes place in a setting provided by an existing organization must be flexible to the needs and drive of the members of those groups. For example, Syrians working in the civil society sector are undertaking critical work for the future of their country. They are building alliances to promote democratic decision-making and leveraging resources to foster peace building. As they tirelessly work around the clock, they balance ongoing concerns for the future of their families and communities. Ensuring that yoga programs are accessible in such contexts requires that an instructor is flexible to the participants’ schedules. For example, we found that workers from one such organization were hesitant to take 60 or 30 minutes for yoga in the days preceding a large conference. People were more willing to take 15 – 20 minute for class, especially if built in as part of the lunch break. It could be easy for a yoga instructor to insist that participants need the usual class length for maximum benefits. Instead, it was important to recognize that their drive to work extensive hours is part of their emotional support; for many in the civil society field their work fuels a sense of hope for the future. In this context, flexible yoga class schedules, including abridged ones, were welcomed as an invitation for relaxation and chance to refuel in a timeline that would not add an psychological burden (e.g., the stress of losing too much time from work that fuels a sense of well-being). 3. Promote individual practices at home In all settings, it was important to provide participants with simple take-home practices. For example, we offered civil society workers handouts that included a ten-minute practice consisting of a few poses to relieve back pain and a breathing exercise. The purpose was to provide a resource for people to develop enhanced relaxation skills. We also found that some participants were shy to fully practice poses in a group setting, even in gender-specific classes. They did, however, report practicing at home and would seek guidance on how to modify or develop their practice further. Similarly, children were enthusiastic to have yoga homework assignments to share with siblings. 4. Welcome conversations – and laughter – during and after yoga class The greatest lesson learned, perhaps, is that laughter is a secret weapon and is a welcomed part of yoga. In a group’s first few classes, participants periodically joked with one another about the challenges of learning a new activity. Sometimes they affectionately teased or challenged one another, and at other times remarked on their own abilities. As a yoga teacher, it was important to welcome their collective energy and compassionately respond and be part of the conversation. In fact, it was in the brief moments when we caught our breath between jokes that someone shared their emotions or reflected on how yoga helped them relax. The social spirit of practicing as a community Although the concept and practice of yoga was new to most of those who participated in classes with us, they demonstrated a willingness to try it and, in many cases, embraced it. We feel that this openness was partially due to Syrian people’s own resilience and partially to the introduction of yoga through trusted existing groups. Syrians within and outside their country regularly demonstrate incredible resilience, meaning that they positively adapt despite circumstances of adversity. Although most Syrians have endured immeasurable loss, the people that we shared yoga with had an incredible ability to laugh and appreciate the moment at hand, an approach that aligns with the philosophies that underpin yoga. The spontaneity and social spirit the participants brought to practice opened space for a deeper experience for all. We feel that because the programs were adapted to local approaches, it will have a more lasting effect as a practice that participants are more likely to turn to for healing in the future. In this context, giving hand-outs with visuals that explain postures for at-home practice becomes even more important. While yoga has a profound role in promoting individual healing, practicing as a community is what keeps alive our humanity and links us together in support of one another – a lesson that we were reminded of in this experience. * Josie Shagwert is the Director for Development at the Center for Civil Society and Democracy (CCSD) in Syria. [1] Syrian refugees, five years into the crisis, Lebanese American University. April 16, 2015. Top image in article: women in a community class, Photo © 2015 Robyn B. Long There is a wonderful expression in Arabic that captures the essence of our lab’s work: “al haraka baraka.” In English this means “movement is a blessing”. This saying may ring particularly true for pediatric cancer patients and survivors who are coping with treatment related side effects such as fatigue or nausea. Access to adapted physical activity programs offers children an engaging and fun opportunity to ease those side effects. In fact, a growing body of research shows that physical activity (such as yoga, aerobic training, and resistance training) improves the health of children at all stages of cancer treatment [1].

This summer I had the honour of sharing yoga with children at the Huda Al Masri Pediatric Oncology Unit in Bethlehem, Palestine. I first met with Dr. Mohammed Najajreh, the head pediatric oncologist, and his team of nurses and social workers. They currently offer a number of activities to brighten the children’s’ moods, such as regular birthday celebrations and visits from storytellers. Dr. Najajreh and his team are expanding supportive care services and were enthusiastic about including yoga among the children’s’ daily activities. As an introduction to the topic, we first reviewed research on the benefits of yoga for children during cancer treatment. These include:

The following day I taught yoga to acute lymphoblastic leukemia patients and their family members. The class focused on simple stretching poses to promote circulation, and mindful breathing activities to enhance relaxation. We also wove in the fun factor and the children tried to trick their mothers in the yoga game ‘mirror mirror’, where one person must mimic another person’s movements. Just like our YTY classes in Calgary, the children joked about new names they invented for the yoga poses. Some of my favorite ones were “the fish who can’t run” and “I’m falling asleep in class”. After the session, parents were eager to review selected poses that they thought could help their child relax before bedtime. I then held shorter one-on-one yoga sessions with patients and their parents to provide more detailed instructions on select poses. Dr. Najajreh and his team are as committed to promoting their patients’ quality of life as they are to treating their diagnoses. They are also open to exploring new interventions that may benefit their patients’ overall health and wellbeing. After the visit, they expressed their excitement at the prospective of including yoga as one such activity that offers multiple benefits to the children and their families. In fact, they recently connected with a local organization specializing in pediatric cancer care services and hope to identify a yoga teacher in the Bethlehem area. It will be exciting to collaborate with the Huda Al Masri Pediatric Oncology Unit and continue the translation of research into a practical program. This visit provided the opportunity for a first meeting. In addition, our lab donated six yoga mats as well as cancer and exercise materials to the unit. Future ideas include partnering with their team to adapt and translate program and training resources for clinicians, families, and yoga teachers. Such collaboration will make resources available in Palestine as well as to Arabic speaking families here in Calgary and, ultimately, expand supportive care programs for children with cancer. This blog was originally featured on the University of Calgary’s Health & Wellness Lab blog. 1. Baumann, F.T., W. Bloch, and J. Beulertz, Clinical exercise interventions in pediatric oncology: a systematic review. Pediatric Research, 2013.74: p. 366–374 2. Moody, K., et al., Yoga for pain and anxiety in pediatric hematology-oncology patients: case series and review of the literature. Journal of the Society for Integrative Oncology, 2010. 8(3): p. 95-105. 3. Thygeson, M.V., et al., Peaceful play yoga: serenity and balance for children with cancer and their parents. Journal of Pediatric Oncology Nursing, 2010. 27(5): p. 276-84. 4. Geyer, R., et al., Feasibility study: the effect of therapeutic yoga on quality of life in children hospitalized with cancer. Pediatric Physical Therapy, 2011. 23(4): p. 375-9. 5. Wurz, A., et al., The feasibility and benefits of a 12-week yoga intervention for pediatric cancer out-patients. Pediatr Blood Cancer, 2014.61(10): p. 1828-34. |

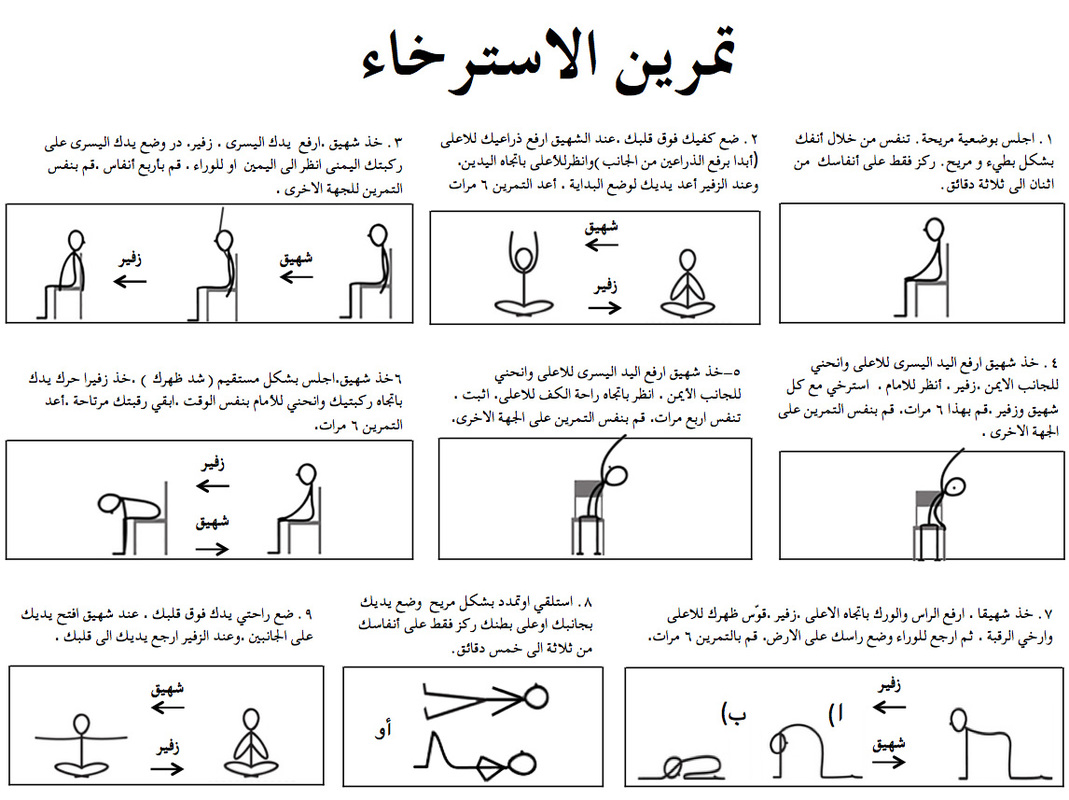

It is a tremendous honor that my article on sharing yoga with Syrians won "Yoga Article of the Year" in Seattle Yoga News. Endless gratitude to everyone who was part of and supported this inspiring project.

Archives

July 2017

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed