|

This article was originally featured on Seattle Yoga News, May 27, 2015. I spent this spring sharing yoga with Syrians seeking safety and refuge in southeast Turkey. I arrived well versed on the four-year Syrian crisis, prepared to teach yoga in Arabic and ready to be of service to people as they healed the wounds of conflict. When I arrived, the crisis was entering its fifth year and more than 220,000 Syrians had lost their lives. The news was always grim. Grief, distress and heartache were omnipresent when I arrived. But the most tangible sentiment I perceived was the sense of support and community that the Syrians brought to each yoga session. After only a few weeks of sharing yoga in local organizations, it became clear that their social spirit was their strongest source for healing. Yoga became a unique opportunity for them to connect with each other as they coped with distress from the crisis. Life in Turkey The Syrians who participated in my yoga classes had all endured immeasurable loss and survived harrowing circumstances. Many had watched in terror as their towns had been bombed or raided while their loved ones were imprisoned, executed or abducted. Many had fled after being targeted by the Syrian regime or extremist groups such as Daesh (the Arabic name for the Islamic State). The crisis disrupted all aspects of their lives; they were forced to postpone marriages, close family businesses and withdraw from university studies. The crisis unraveled the social fabric of everyday life; families were torn apart and communities were polarized by new religious and ethnic lines. One participant shared that her husband was en route to seek asylum in another country — a dangerous journey — and she had not heard from him in one month. Unfortunately, life in Turkey did not guarantee safety or hope for the future. Many people concealed their identities by taking on new official names and using pseudonyms in public. A large proportion of the 1.8 million Syrian refugees in Turkey currently live in camps that offer basic levels of shelter, food and healthcare. The majority of people I met, however, lived in urban areas without access to even these basic resources. Even within this context, people warmly welcomed me into their organizations and homes to share yoga. Yoga for Syrians A growing number of humanitarian agencies are discussing the need for conflict and post-conflict programs to incorporate ‘psychosocial services’ – a broad term used to encompass a range of activities that increase emotional resilience. In this case, Syrian health and civil society nonprofits were receptive to yoga as a psychosocial activity that promotes relaxation techniques. I collaborated with organizational representatives to discuss the context of classes, give presentations on the psychosocial benefits of yoga and schedule classes. Within this framework, I taught one to two yoga classes each day, each one lasting anywhere from 15 to 60 minutes. I offered daily classes to employees in a civil society organization, and periodic classes at youth schools and women’s clubs. Adult classes typically included four to ten participants per class whereas the classes in schools ranged from 20 to 50 students. The sequences consisted of breathing practices, guided relaxation and simple poses that could be done wearing normal attire. Over the course of a few weeks, I introduced participants to home practices and provided handouts in Arabic. Handouts for adults were short relaxation practices to address the most common ailments reported: back pain and difficulty sleeping. Children received copies of breathing practices (with a fun twist) that we did during class. Classes were positively received across organizations. Nonprofit employees reported better concentration in their offices after lunchtime yoga sessions. School teachers expressed amazement at how effectively the children learned to focus on their breath, and they enthusiastically asked for resources to continue yoga activities. Children shared that they not only enjoyed the take-home practices, but also shared them with siblings. Women described a weight being lifted from their chests when they completed breathing practices before bed. However, there were moments in several classes when the grief was so palpable that I had to pause and take a few deep breaths to ground myself while teaching. This sorrow was particularly salient when I was teaching a women’s group whose children had been abducted by Daesh. The walls where we practiced yoga were laminated with photos of smiling children, their names and ages inscribed at the bottom of each image. Their mothers were all from the same town and it was unlikely any of them would ever see their beloved children again. The feeling that was more substantial than grief was the social spirit that the Syrians brought into every yoga session. During classes, people would affectionately joke with one another about the challenges of the new activity. They playfully debated if yoga could cure conditions such as a smoker’s cough. After classes, participants were eager to keep spending time together. Women served cake and tea as they caught up on news about each other’s families and quizzed me enthusiastically about my family plans. Nonprofit workers organized post-yoga luncheons and city excursions where we discussed yoga philosophy. At the conclusion of their classes, children sang and performed dabke, an Arab tradition that consists of holding hands and dancing in a circle. The solace and joy they created and found in each other’s company was unmistakable. Community and Collective Healing Syrians in Turkey are seeking at least two avenues for healing. First, they are searching for ways to cope with their individual experiences of violence and loss. Second, they are processing a collective memory of painful events and injustices — all while striving to build new communities. Syrians are actively building support networks that reinforce the significance of collective healing after a collective trauma. In fact, a growing body of research on collective trauma emphasizes that psychological outcomes are more closely linked to social support than with an individual’s history of direct exposure to events like violence or torture. The World Health Organization even recommends large-scale programs to promote healing from trauma as a necessity to prevent further violence, and as a prerequisite to post-conflict reconciliation. Integrating yoga into programs for survivors of collective trauma is a relatively new type of intervention. In the U.S., the majority of trauma related programs (yoga and non-yoga) are modeled after a biomedical framework focused on the individual’s experience. The Syrians taught me the importance of moving beyond this structure so that yoga also fosters collective healing. In each of the settings where I taught, it was important to ensure yoga was part of and contributed to existing support mechanisms. Yoga simply represented an opportunity for a social activity that led to community discussion and goal setting. The social spirit that Syrians brought to our yoga sessions created an environment that nurtured resilience and healing — for them, and for their communities. Their sense of togetherness reminded me of a quote by my teacher, Mr. T. K. V. Desikachar, on the topic of faith and healing: “…the energy of togetherness is much more than the sum of individual energies” [1]. I hope that all of my future yoga classes vibrate with such a strong sense of togetherness, from Syria to my new home in Seattle. [1] Desikachar, T. K. V. and Martyn Neal (2001). What are we seeking? Krishnamacharya Yoga Mandiram, Chennai, India.

0 Comments

Robyn Long with Josie Shagwert* This post is based on my experience sharing yoga with Syrians who have sought safety and refuge in Turkey. In Gaziantep and Şanliurfa, two cities now home to approximately 500,000 Syrians each, I taught yoga classes for civil society groups, women’s clubs, and schools in the spring of 2015. I am honored that my co-author Josie Shagwert has contributed her insight on the experiences of community development and life in exile as a member of a civil society organization promoting peace and democracy in Syria.

Yoga is a mindful activity that supports the interrelated physical, social, and emotional needs of people who have experienced traumatic events, such as war, displacement, and resettlement. Yoga practices offer survivors of such events an opportunity to experience relaxation and a sense of peace within themselves. Also, through yoga, participants have an opportunity to learn tools, such as breathing practices, which they can draw upon to address post-traumatic stress symptoms, such as an accelerated heartbeat or difficulty sleeping. Our experience in yoga programs for Syrians displaced by war offers insight and lessons for future programs and instructors in similar contexts. Namely, in communities displaced by conflict and violence, yoga programs focused on healing must be linked with existing networks and culturally-rooted practices. These networks and practices, formal and informal, are powerful resources for support and provide a sense of normalcy as people adjust to life in a new country. In yoga programs tailored for survivors of trauma and grief, teachers often discuss the art of “holding space” for participants. The concept of holding space spans the physical setting (e.g., how to arrange the yoga mats) to the emotional environment (e.g., how we foster a compassionate, stable, and non-judgmental atmosphere for participants to work through their experiences). The emphasis in these contexts is usually on the individual. For example, an instructor may provide ten minutes at the end of a class for relaxation, perhaps with a guided visualization or breathing practice. Afterwards, the teacher would be available for participants to discuss any emotions that surfaced or their experiences during the practice. When offering yoga to communities displaced by war, our recent experience suggests that yoga instructors should shift their focus of holding space from the individual to the group level. In fact, we found that it was critical for the instructor to be part of and contribute to the collective space that communities had already created. This sometimes meant discarding static notions of the “best” ways to practice in favor of adapting to the local atmosphere and practices, including making space for conversation and comments during class and doing traditional dances afterward. By adapting in these ways, both the instructor and the yoga experience gain more traction, trust and legitimacy in these settings – and thus are able to more fully contribute to healing for the participants. Yoga for Syrian communities in exile Syrians who have sought safety in Turkey face an array of daily challenges. Turkey is host to the largest number of Syrian refugees, with nearly 1.8 million registered in the country [1]. Many of the refugees live in camps that provide at least basic levels of food, shelter, and healthcare. Many, however, live outside of the camps and lack access to healthcare, stable shelter, employment, etc. Very few speak the local language fluently and nearly everyone has to adapt to new living arrangements and assume increased family responsibilities. Each person has a harrowing story of escape and has lost or been separated from loved ones. People are simultaneously building a new community while striving to promote stability in their homeland. In this context, they have formed support networks in everyday environments such as work, school, and informal social settings. To promote the wellbeing of Syrians in this context, we offered yoga in a range of group settings, such as the workplace, women’s clubs, and schools. Yoga was welcomed by multiple groups as an activity for people to learn skills for relaxation and healing. Several basic considerations were taken into account when designing the classes:

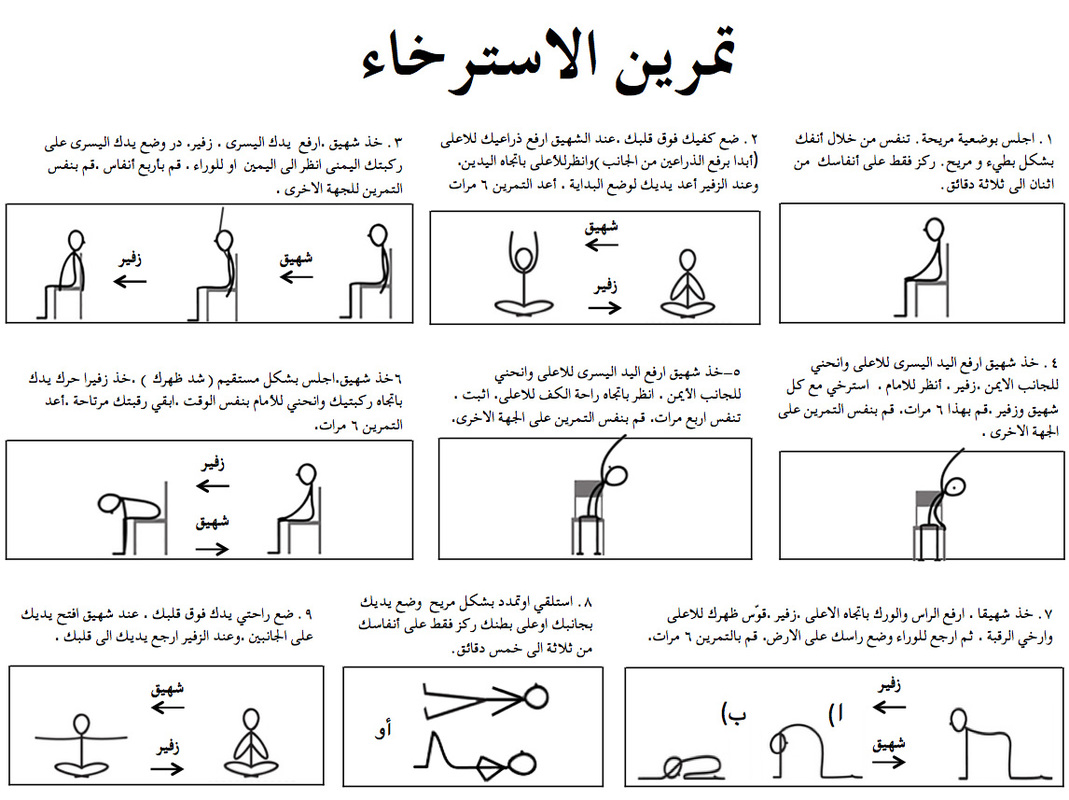

1. Integrate traditional social activities into yoga Social activities are a critical aspect of community building in Syrian culture. For example, after a club meeting, women typically converse over tea and snacks. In a school setting, children often sing and perform dabke, an Arab tradition that consists in dancing in a circle while holding hands. These collective activities are particularly important for Syrians displaced by war because they promote a sense of solace as a familiar activity from home. Creating time for social activities after yoga provides a grounding activity for participants after individual relaxation and reflection. In our experience, the activities happened organically and they brought participants together to support one another – which was beneficial as new emotions can surface during or after yoga. It was also during these activities that participants expressed the impact yoga had for them. For example, it was in a circle while dancing dabke that girls at school remarked on how yoga made them feel energized, relaxed, or “free to breathe”. 2. Remain flexible to the time and needs of organizations Yoga that takes place in a setting provided by an existing organization must be flexible to the needs and drive of the members of those groups. For example, Syrians working in the civil society sector are undertaking critical work for the future of their country. They are building alliances to promote democratic decision-making and leveraging resources to foster peace building. As they tirelessly work around the clock, they balance ongoing concerns for the future of their families and communities. Ensuring that yoga programs are accessible in such contexts requires that an instructor is flexible to the participants’ schedules. For example, we found that workers from one such organization were hesitant to take 60 or 30 minutes for yoga in the days preceding a large conference. People were more willing to take 15 – 20 minute for class, especially if built in as part of the lunch break. It could be easy for a yoga instructor to insist that participants need the usual class length for maximum benefits. Instead, it was important to recognize that their drive to work extensive hours is part of their emotional support; for many in the civil society field their work fuels a sense of hope for the future. In this context, flexible yoga class schedules, including abridged ones, were welcomed as an invitation for relaxation and chance to refuel in a timeline that would not add an psychological burden (e.g., the stress of losing too much time from work that fuels a sense of well-being). 3. Promote individual practices at home In all settings, it was important to provide participants with simple take-home practices. For example, we offered civil society workers handouts that included a ten-minute practice consisting of a few poses to relieve back pain and a breathing exercise. The purpose was to provide a resource for people to develop enhanced relaxation skills. We also found that some participants were shy to fully practice poses in a group setting, even in gender-specific classes. They did, however, report practicing at home and would seek guidance on how to modify or develop their practice further. Similarly, children were enthusiastic to have yoga homework assignments to share with siblings. 4. Welcome conversations – and laughter – during and after yoga class The greatest lesson learned, perhaps, is that laughter is a secret weapon and is a welcomed part of yoga. In a group’s first few classes, participants periodically joked with one another about the challenges of learning a new activity. Sometimes they affectionately teased or challenged one another, and at other times remarked on their own abilities. As a yoga teacher, it was important to welcome their collective energy and compassionately respond and be part of the conversation. In fact, it was in the brief moments when we caught our breath between jokes that someone shared their emotions or reflected on how yoga helped them relax. The social spirit of practicing as a community Although the concept and practice of yoga was new to most of those who participated in classes with us, they demonstrated a willingness to try it and, in many cases, embraced it. We feel that this openness was partially due to Syrian people’s own resilience and partially to the introduction of yoga through trusted existing groups. Syrians within and outside their country regularly demonstrate incredible resilience, meaning that they positively adapt despite circumstances of adversity. Although most Syrians have endured immeasurable loss, the people that we shared yoga with had an incredible ability to laugh and appreciate the moment at hand, an approach that aligns with the philosophies that underpin yoga. The spontaneity and social spirit the participants brought to practice opened space for a deeper experience for all. We feel that because the programs were adapted to local approaches, it will have a more lasting effect as a practice that participants are more likely to turn to for healing in the future. In this context, giving hand-outs with visuals that explain postures for at-home practice becomes even more important. While yoga has a profound role in promoting individual healing, practicing as a community is what keeps alive our humanity and links us together in support of one another – a lesson that we were reminded of in this experience. * Josie Shagwert is the Director for Development at the Center for Civil Society and Democracy (CCSD) in Syria. [1] Syrian refugees, five years into the crisis, Lebanese American University. April 16, 2015. Top image in article: women in a community class, Photo © 2015 Robyn B. Long This is the first of several posts that are based on my experience sharing yoga with Syrians who have sought safety and refuge in Turkey. In Gaziantep and Sanliurfa, two cities now home to approximately 500,000 Syrians each, I taught yoga classes for civil society groups, women’s clubs, and schools in the spring of 2015.

In my global travels, I have become increasingly attentive to the different meanings “yoga” has for people from diverse religious, social, and cultural backgrounds. I have taught yoga within the walls of churches in Canada, and the circles of Islamic societies in the Middle East. My most recent experience teaching yoga within Syrian communities reinforces the importance of focusing on the essence of yoga as service by ensuring that it is accessible in an array of cultural contexts. I wear two hats when developing community yoga programs. The first hat is that of a grassroots international development practitioner. This involves collaborating with partner organizations to brainstorm and evaluate the best approaches to tailor a program so that it is meaningful to participants, and accepted by their communities. The second hat that I wear is that of a yoga teacher and student within the tradition of Sri Krishnamacharya. Sri Krishnamacharya’s son, Mr. T.K.V. Desikachar, my teacher and founder of theKrishnamacharya Yoga Mandiram (KYM) in India, has dedicated his life to ensuring yoga is accessible and relevant to people from all corners of the globe. During our training, Mr. Desikachar and the KYM faculty often challenged us to assess whether a certain activity or action was or was not “yoga”. In the end, the conclusion that we always came to was not defining yoga by a style or set of postures but instead understanding yoga as a form of service [1]. Naming and Explaining Yoga Prior to embarking on my work with Syrian organizations, I decided to use the term yoga for classes. My decision was based on previous experiences teaching yoga in Palestine, where the term was accepted. Over the last few years, there has also been an emergence of yoga studios throughout the Middle East. Once I began, one Syrian organization openly welcomed yoga and we had classes almost daily. Unfortunately, I did encounter resistance to yoga within other organizations. The European director of a school for Syrian children, supported by a European-Christian association, canceled yoga classes under the suspicion that yoga may contradict their faith. I was unsuccessful in reinstating those classes despite my best efforts in clarifying that yoga was not religious or even linked to Hinduism (as a note, Hinduism rejected yoga as a school of thought in India because the ancient yoga texts do not insist that God exists). Disappointed by the cancellation of yoga in one school, I recognized that yoga might not be an appropriate term for all organizations. What then, should classes be called? I reflected on what I had learned during my teacher training at KYM. In therapeutic contexts, yoga is a holistic, individualized practice to improve wellbeing. It offers approaches to healing by bringing the mind to stillness and reducing suffering through a strengthened relationship with oneself. In fact, Mr. Desikachar has described yoga as “a relationship with our own self”. In the tradition of Krishnamacharya, we employ a variety of practical tools (e.g., postures, breathing, meditation, mantra) that empower participants to take action in their own health and healing. After consulting with contacts from Syrian organizations, I decided that it would be best to start using language that reflected the tools employed in class and that resonated with the organization’s services. I described classes as opportunities for participants to focus on themselves and learn relaxation skills such as breathing techniques. This explanation aligned with the growing emphasis on psychosocial programming by Syrian groups. After some simple wording adjustments, sessions were welcomed in a range of settings including other schools and nonprofit organizations. The following are two examples of how language was adapted. Sessions for children were held during physical education (P.E.) class and called “exercise and relaxation”. In advance of classes, I developed a set of cards with images of postures and breathing practices in Arabic (see images below). When I met with directors and teachers, I shared the cards and explained that the progression of a class moved from active postures into guided breathing while sitting or lying down. After classes, teachers remarked that the cards were engaging and fun for students and that the sequence was effective in leading them into relaxation. They also shared that the cards were useful resources in continuing the classes after my volunteer time ended. In addition, I named the adult classes “relaxation practices”. Prior to starting classes, I gave a presentation for organizational representatives that outlined the class format and highlighted how relaxation practices, such as breathing techniques, connect to the nervous system and benefit people who have experienced traumatic events. During classes, I selected postures that would be easy to learn, comfortable to do in regular clothing, and safe to practice at home without props. Coincidentally, several of the postures corresponded to the movements performed in the Muslim prayer. This was only partially intentional because some of these yoga postures are frequently used in therapeutic settings (e.g., Uttanasana and Cakravakasana, which are similar to the Muslim prayer movements of Ruku and Sujud). Participants approvingly remarked on this similarity and shared that it made learning some of the movements less intimidating. In terms of language used during classes, I did not use any Sanskrit terms – something commonly done in yoga. I named postures and breathing practices in children’s classes after animals and shapes. Several Syrian representatives in partner organizations vetted the names to ensure that they were culturally appropriate. In adult classes I simply described the movement, e.g., “arm raises” and “forward bend”. In a few instances, participants did ask me “Is this similar to yoga?” I responded that yes, many would call it yoga, including myself if I were teaching back home. I also shared that I had studied yoga, as well as other forms of mindfulness and relaxation, in India, Canada, and the US. Though my experience was confined to a few weeks, this discussion never had negative outcomes. In fact, it led to further discussions on the differences between various mind-body programs. At that point, I asked people what they would prefer classes be called; the consensus was always to keep the name as it was (i.e., not yoga) given potential sensitivities that conservative religious groups might have. Focusing on Service In the spirit of yoga as service, it was important to let go of my labels and definitions of yoga. While I am adamant that “exercise” is not “yoga”, exercise was the appropriate term to use in conjunction with relaxation for the children’s classes. As Mr. Desikachar noted, “...there are many possible ways of understanding the meaning of the word yoga. Yoga has its roots in Indian thought, but its content is universal because it is about the means by which we can make the changes we desire in our lives. The actual practice of yoga takes each person in a different direction” [2]. Just as the practice for each person is different, so is the most appropriate approach to offering programs in different cultural settings. As a yoga teacher, I strive to teach to the needs of participants in my class on that day, in that moment. I am grateful to have learned more about the art of adapting classes beyond the physical postures and breathing practices, but also my language and approaches to partnering with diverse organizations. These adaptations ensure the programs were accessible and welcomed by an array of community groups. [1] Mr. Desikachar discussed the importance of not defining yoga by style but instead as a service in an interview on Yoga Chicago. [2] The Heart of Yoga: Developing a Personal Practice, T. K. V. Desikachar, 1999. Top image: Gaziantep, Turkey, Photo © 2015 Robyn B. Long |

It is a tremendous honor that my article on sharing yoga with Syrians won "Yoga Article of the Year" in Seattle Yoga News. Endless gratitude to everyone who was part of and supported this inspiring project.

Archives

July 2017

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed